Imagine being a resident of Bethlehem 2,000 years ago. One cold evening you hear a commotion outside. You open the door and see smelly sheep herders shouting to the whole neighborhood that a poor virgin from Nazareth living in a barn down the street has just given birth to the new king of Israel. It would be an understatement to call such a thing unexpected.

“God works in mysterious ways,” they say. We hear this phrase so often it has become a cliché. It’s not so much that God is mysterious—we can know much about him through his self-revelation in Scripture—but that God often acts mysteriously. The fact that he is so large and wise means we can never quite predict what he will do. God very often surprises us.

This is nowhere more true than in the advent of Jesus Christ. It is an unexpected tale. God moves through an unexpected woman from an unexpected town to produce an unexpected child heralded by unexpected messengers.

God does not subvert our expectations just for the fun of it. When we sense God working in mysterious ways, we would do well to take it as an opportunity to reconsider our assumptions. We might assume that a poor woman is less dignified than a rich one, a manger is less noble than a palatial nursery, or a shepherd is less reliable than a scholar.

All of the figures in the nativity story carry their own surprises, and each one can expose our misguided assumptions about how God works. This makes Christmas a prime opportunity to open our minds and hearts to the possibilities of God.

Unexpected visitors

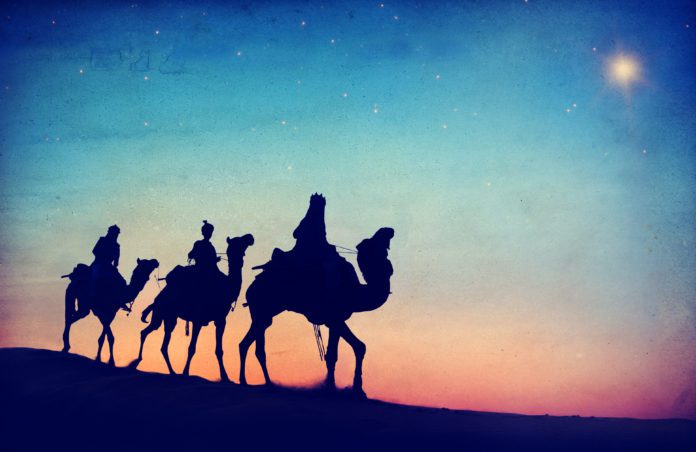

The magi take centerstage in the first half of Matthew 2, and nothing could have been more unexpected than pagan astrologers from Babylon being the first to herald the arrival of the Messiah to the nation of Israel. The magi, for their part, seem to have no idea what they were getting themselves into.

They simply want to be diplomatic by congratulating the king on his new son. They are completely unprepared for the fact that this child is not to be found in Herod’s palace in Jerusalem. Thus, their diplomatic mission unexpectedly becomes embroiled in political intrigue. Where is Herod’s replacement—or in his mind, usurper?

Although Herod has no baby to show to the magi, he is undeterred. The religious experts will know where to find the boy. “So, he assembled all the chief priests and scribes of the people and asked them where the Messiah would be born” (Matthew 2:4).

The experts report to the king that the prophet Micah foresaw that this ruler would come from Bethlehem. So now the magi’s visit to Jerusalem has become an epic game of hide-and-seek through the Judean countryside. Only by the miracle of the guiding star are the royal delegates successful in their quest.

Matthew 2:11 tells us that, “entering the house, they saw the child with Mary His mother, and falling to their knees, they worshiped Him. Then they opened their treasures and presented Him with gifts: gold, frankincense and myrrh.” Royal gifts befitting a royal figure could not have been more out-of-place in this humble Bethlehem home.

The scandal

For those us that have grown up with this story, it may have lost its force. But the scandal is not lost on the original audience of Matthew’s gospel: The first ones to bow down before the Jewish Messiah and honor him as king were not Jewish at all.

In fact, they are pagans from Babylon, who read of his birth in the stars! Why would God use, of all people, polytheistic astrologers to announce the Christ Child? We need only read the statement of Peter to Cornelius in Acts 10:28 to recall how lowly most Jews thought of non-Jews. The first “apostles” of Jesus’s birth were dirty shepherds and now these pagans! Surely there are better messengers God could use!

Who would we choose?

Who should have been most excited to welcome the Christ Child? The Jewish religious leaders, of course. But what, in reality, was their reaction to the news? “When King Herod heard this, he was deeply disturbed, and all Jerusalem with him” (Matthew 2:3).

Now when Matthew says, “all Jerusalem,” he does not mean the whole populace. It is as when we say, “There was turmoil today in Washington D.C.” We do not mean the people but the leaders—Capitol Hill, the elite, the heavy hitters. In Jerusalem, this means the high priests, the religious experts (scribes), and the elders of the people. This is who composed the Sanhedrin, the city council of Jerusalem.

We can understand why Herod is not excited to hear that a new, rival king has come on the scene. The real question is: Why is the Jerusalem leadership disturbed along with him?

There are several who claimed the Messianic throne in the decades before Jesus, men such as Theudas and Judas the Galilean of Acts 5:36 who led revolts against the Roman occupation. This social turmoil has placed Judea on thin ice with Rome. Surely a new contender for the throne will only make matters worse. For the religious leaders in Jerusalem, the status quo is the best they can hope for.

And so, when confronted with the possibility that the foretold Messiah has finally come, these priests and scribes can’t help but imagine what another failed rebellion could bring. They hold up hope against fear, and they choose fear.

Hope or fear

They are the religious leaders of all Israel. They operate the temple and guide the people in all religious matters. The guardians of God’s truth and wisdom should be the ones most looking forward to their Messiah, but instead they turn out to be the ones most dreading him.

The religious leaders are mentioned only briefly in this narrative, appearing in verse 3 where they share Herod’s consternation and verse 5 where they acknowledge the prophecy about the Messiah. Nonetheless, they are still some of the most important figures in the story because they stand in contrast to those whom God uses instead.

If the religious leaders of Jerusalem will not welcome Jesus, God will send someone who will, the most unlikely of heralds. As Jesus says, “I tell you, if [my disciples] were to keep silent, the stones would cry out!” (Luke 9:40). God’s people keep silent, and so God raises up stones to cry out.

God’s lesson for us here is best seen in the contrast between both sides of the coin. The very people entrusted to lead the people of God in matters of faith and practice are the ones most troubled when God finally shows up, while the despised “outsiders” are called in by God to inaugurate the future.

To an elite who assumes they are the sole guardians of God’s truth in the world, the role of the magi in these events is a big wake-up-call. Perhaps this is the same wake-up-call we need today. God works in mysterious ways, but we do not like mystery. We like certainty and predictability. Uncertainty drives us to fear, just like the religious leaders.

God does not only use the people we say he can. We are not to blindly follow people just because of their office or title, without discerning if their lives are showing the fruit of the Spirit. Nor are we to dismiss what “outsiders” might have to say and risk missing out on what God might be telling us. The spiritual practice of seeking—rather than fearing—wonder and mystery in the world can give us “eyes to see and ears to hear” what God is doing all around us in unexpected ways.

Christmas is an opportunity to expect the unexpected, to view every impossibility as possible, and to see every unlikely person as a possible vehicle for God to teach us truth.

David Reed has served since 2016 as an elder at North Park Community Church, a USMB congregation in Eugene, Oregon. He currently serves as the council chair. He received his masters of divinity from Western Seminary in Portland, Oregon, and his masters of philosophy from Bushnell University in Eugene. Reed is a stay-at-home dad for his son.

Well written, David. I enjoyed your perspective on the text, its context, and your invitation to seek rather than fear in these days. I’ve wondered if Daniel, trained as he was in astrology by Chaldean seers 600 years earlier, might also have trained them to look for God’s foretold Messiah in the stars. That would have been another highly unexpected method God might have used to draw the nations to worship his Son.